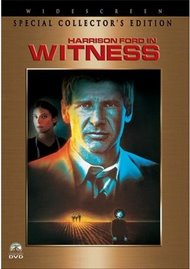

“Witness” seems, at first glance, to depict a story of the encounter of two contrasting ordinary worlds in 1984: the ordinary world of an Amish community and the world of Philadelphia. Rachel (Kelly McGillis) and her extended family personify the separated Amish world. John Book (Harrison Ford) and his extended family (especially his sister Elaine and his partner Sergeant Carter, but also his fellow policemen, boss Paul Schaeffer, McFee and Fergie) personify the world of Philadelphia, the City of Brotherly Love.

First a death and then a murder set up the encounter and take both Rachel and John out of their ordinary worlds. While the first death, of Rachel’s husband Jacob, seems of natural causes, the murder in the train station bathroom clearly wasn’t. Samuel’s witnessing it opens up the story to the adventure the story goes on to tell.

“Witness” seems to be a movie about having to make choices, rather than make judgments, or make decisions. For example, either life in the city or life on the farm. The culture of life versus the culture of death.

However, upon further exploration of the meaning of the story, at least four perspectives on life and the beginning bases for decisions we make in it are noteworthy.

The first perspective I notice I will call “value.” The Amish community and the City of Brotherly Love certainly present a contrast in what and who is valued. One prominent contrast is bartering, for lack of another word, in the Amish community as depicted in the barn raising versus pursuit of money whatever the costs as represented by the cops who have lost their meaning stealing drug chemicals worth $22 million. Eli’s character represents the Amish values and he is intent on teaching them to Samuel.

The second perspective I will call “mission.” The Amish community’s mission is to save John from dying and bring him back to life. John’s is to seek justice, i.e., protect Rachel and Samuel from the bad cops and expose the killers of his partner. The mission of the bad cops is to avoid the exposure.

The third perspective I will call “purpose.” In the City of Brotherly Love, Rachel and Samuel experience lives with very different purposes than theirs. For example, compare their happy valley with the “Happy Valley” bar. Once in the Amish community, John experiences a community life with a clearly different purpose. For example, “whacking” is not a normally useful skill on a farm.

The fourth perspective I will call “vision.” Samuel personifies vision. He sees the statue of the archangel Michael bearing the soul of a fallen soldier (Angel of Resurrection) in the train station before he sees the murder in the bathroom. When John is pulled out of Elaine’s car by Eli, the image of the fallen warrior is repeated. Though John tells Samuel to run to Daniel’s farm for help, when shots are fired Samuel knows to come back. Eli does not tell him to pull the bell, he shows him with a hand signal. And, finally, John shows Samuel to Schaeffer in the end, asking him if he’s going to kill the boy too.

Viewing “Witness” from these four perspectives, “value,” “mission,” “purpose,” and “vision,” I see this story as a beginning point to decision-making because it helps us become conscious of our own ordinary worlds and some of the matters we must all face when we are called out of them.

When we do become aware of the differences, it seems that if we approach issues as a matter of choice, we are talking “either/or.” For example, John Book tells Rachel that if they had made love the night before, either he would have to stay or she would have to leave.

For sure in our blogs or comments, we will discuss the “either/or” approach, especially in contrast to the approach of “both/and.” “High Noon” seems to take the former approach. “It’s A Wonderful Life” seems to take the latter one.

What I like about “Witness” is that it well depicts and personifies the first stage of discovering a key feature of the Decision-Maker’s Path. For me that feature is that “where we are coming from” is a realization that our ordinary world is somehow dis-integrating.

Once we see ourselves in that position, we know we are at the beginning of a process that will call on us to make a decision. I don't see John or Rachel ready to make a decision to integrate their lives. Though they tasted it, within the terms of the story, they chose not to go beyond that and slipped back into their separate, ordinary worlds. No doubt Eli was happy with this, as was Daniel. But what about Samuel?

Is Samuel's vision of the world changed forever? Does he not have new insights into what is valuable, what mission he may be called on to undertake in life, what his purpose is as he relates to others, and what his future is going to be like?

When we identify with him, we face the dis-integration he has witnessed and the task of integrating all of what he has learned that I believe only making decisions will achieve.

Perhaps like Samuel, at the beginning of the path to a decision, we may want to take on the role of the fool, not like Uncle Billy's "silly, stupid, old fool" but rather like George Bailey when he is reborn in "It's A Wonderful Life": fun, insightful, and young at heart.

What do you think?

© 2007 John Darrouzet

First a death and then a murder set up the encounter and take both Rachel and John out of their ordinary worlds. While the first death, of Rachel’s husband Jacob, seems of natural causes, the murder in the train station bathroom clearly wasn’t. Samuel’s witnessing it opens up the story to the adventure the story goes on to tell.

“Witness” seems to be a movie about having to make choices, rather than make judgments, or make decisions. For example, either life in the city or life on the farm. The culture of life versus the culture of death.

However, upon further exploration of the meaning of the story, at least four perspectives on life and the beginning bases for decisions we make in it are noteworthy.

The first perspective I notice I will call “value.” The Amish community and the City of Brotherly Love certainly present a contrast in what and who is valued. One prominent contrast is bartering, for lack of another word, in the Amish community as depicted in the barn raising versus pursuit of money whatever the costs as represented by the cops who have lost their meaning stealing drug chemicals worth $22 million. Eli’s character represents the Amish values and he is intent on teaching them to Samuel.

The second perspective I will call “mission.” The Amish community’s mission is to save John from dying and bring him back to life. John’s is to seek justice, i.e., protect Rachel and Samuel from the bad cops and expose the killers of his partner. The mission of the bad cops is to avoid the exposure.

The third perspective I will call “purpose.” In the City of Brotherly Love, Rachel and Samuel experience lives with very different purposes than theirs. For example, compare their happy valley with the “Happy Valley” bar. Once in the Amish community, John experiences a community life with a clearly different purpose. For example, “whacking” is not a normally useful skill on a farm.

The fourth perspective I will call “vision.” Samuel personifies vision. He sees the statue of the archangel Michael bearing the soul of a fallen soldier (Angel of Resurrection) in the train station before he sees the murder in the bathroom. When John is pulled out of Elaine’s car by Eli, the image of the fallen warrior is repeated. Though John tells Samuel to run to Daniel’s farm for help, when shots are fired Samuel knows to come back. Eli does not tell him to pull the bell, he shows him with a hand signal. And, finally, John shows Samuel to Schaeffer in the end, asking him if he’s going to kill the boy too.

Viewing “Witness” from these four perspectives, “value,” “mission,” “purpose,” and “vision,” I see this story as a beginning point to decision-making because it helps us become conscious of our own ordinary worlds and some of the matters we must all face when we are called out of them.

When we do become aware of the differences, it seems that if we approach issues as a matter of choice, we are talking “either/or.” For example, John Book tells Rachel that if they had made love the night before, either he would have to stay or she would have to leave.

For sure in our blogs or comments, we will discuss the “either/or” approach, especially in contrast to the approach of “both/and.” “High Noon” seems to take the former approach. “It’s A Wonderful Life” seems to take the latter one.

What I like about “Witness” is that it well depicts and personifies the first stage of discovering a key feature of the Decision-Maker’s Path. For me that feature is that “where we are coming from” is a realization that our ordinary world is somehow dis-integrating.

Once we see ourselves in that position, we know we are at the beginning of a process that will call on us to make a decision. I don't see John or Rachel ready to make a decision to integrate their lives. Though they tasted it, within the terms of the story, they chose not to go beyond that and slipped back into their separate, ordinary worlds. No doubt Eli was happy with this, as was Daniel. But what about Samuel?

Is Samuel's vision of the world changed forever? Does he not have new insights into what is valuable, what mission he may be called on to undertake in life, what his purpose is as he relates to others, and what his future is going to be like?

When we identify with him, we face the dis-integration he has witnessed and the task of integrating all of what he has learned that I believe only making decisions will achieve.

Perhaps like Samuel, at the beginning of the path to a decision, we may want to take on the role of the fool, not like Uncle Billy's "silly, stupid, old fool" but rather like George Bailey when he is reborn in "It's A Wonderful Life": fun, insightful, and young at heart.

What do you think?

© 2007 John Darrouzet

No comments:

Post a Comment